|

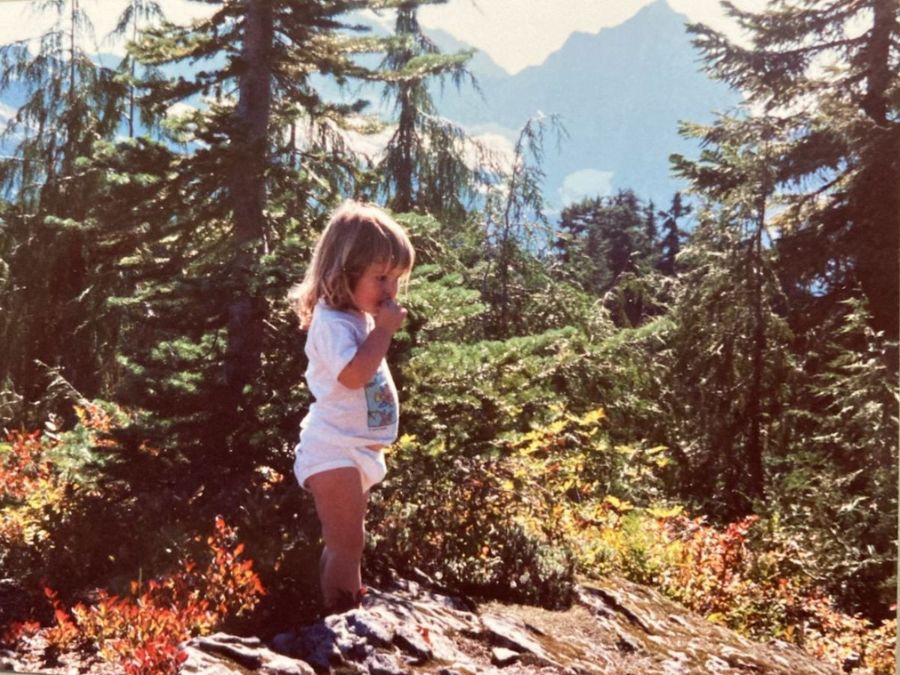

This essay is adapted from a 2017 newsletter. When I was a child, I saw the magic at work in everything. The door between the physical and imagined was open and the world was full of wonder. There was little difference between the magic of tide pools, methodically explored in Tevas and fleece on an overcast afternoon, laminated species key in hand, and the magic of a backyard fairyland, where I might spend equally serious hours exploring the fairy kingdom and serving feasts from the garden in raspberry goblets and bowls carved from hard, green apples. I found worlds in the secret colors inside clam shells, in the geode's prickly center, in the lush abstractions of Georgia O'Keefe's erotic flowers, which I carried in a pocket-sized art book that must have come from a museum gift shop. I kept beach stones and horse chestnuts for pets.

But, of course, I grew up. In biology and physics classrooms we learned beautiful theories, but never spoke of wonder. In English class we read fiction, but wrote only critical essays. Each subject in turn closed its door on imagination. I learned many things in school, but forgot magic. Looking the other day at the wild topography of the rye breads, I felt an upwelling of the old wonder. The loaves cooling on the rack before me were as beautiful as any purple-hearted clam shell. They were made with intellect—with a practical understanding of temperature and time, of enzymes, yeast, and bacteria—and with the visceral knowledge of long practice. Science and intuition, fact and metaphor, both. Bread baking, I thought, might be a kind of practical magic. Sophie Owner | Baker Comments are closed.

|

BY SUBJECT

All

|