|

Nina lives in the Gulf Islands. She found my name in a zine her daughter brought her, Baking for Biodiversity, by the Portland writer and baker Katie Gourley. She liked that I run the bakery by bicycle—she thought I milled my flour by bicycle, too!—and so she called up her local library and asked the librarian to find my phone number. She doesn’t have a tv, a computer, or a cell phone; she listens to Amy Goodman in the morning on a Bellingham radio station, and sometimes a little music afterwards if it’s any good. Doesn’t have a car and, at 80, no longer rides her bike. She bakes bread every other week—pain sauvage, “because I’m wild!”—in a 94 year old electric, cast iron oven in her 100 year old house. She is a photographer. She mentioned, in passing, that in her youth, in London, she photographed The Beatles. Pain sauvage is wild fermented bread, made without commercial yeast or sourdough. The dough ferments with the yeast and bacteria present in the grain. This is how idli is traditionally made, and injera. I heard once of a baker in Italy who left his mixing bowl of dough to wild ferment every night. I’ve never made a wild fermented wheat bread, so I’m copying out Nina’s instructions here as told to me, with all her particulars. If you decide to make her pain sauvage, you will, of course, need to adapt the ingredients and process to your own kitchen. NINA's PAIN SAUVAGE

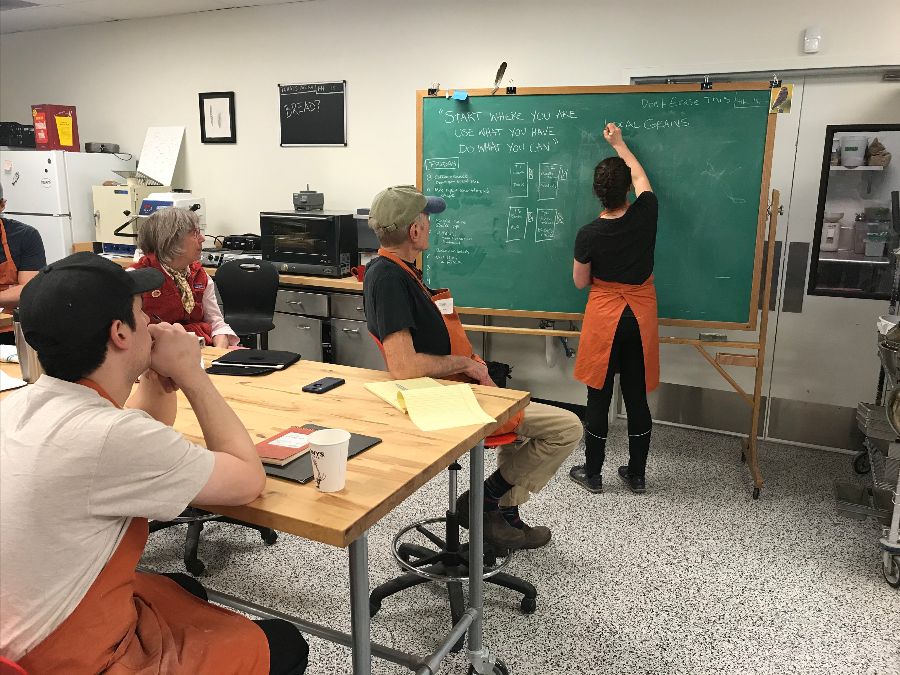

Day 1 Mill 1/3c rye, 1c emmer, and 1c red fife wheat into coarse meal. Mix with an equal volume of very cold water and ferment overnight at approximately 20°C for 20 hours. Mix 4c red fife wheat flour with 4c water. Ferment overnight at approximately 20°C for 20 hours. Day 2 Mix the overnight ferments, 3tsp sea salt, and 6c of red fife wheat flour with a wooden spoon. Let sit for an hour. Knead for 5 minutes, and then stretch and fold every hour for 5 hours. Leave out for another three hours or so before putting the dough into the refrigerator overnight. Day 3 Take dough out, let sit for half an hour. Turn dough onto a table dusted with bran. Cut into 4 pieces. Grease 4 round, glass pans and place dough into them. Scatter flax seed on top. Meanwhile, preheat the oven to 600°F. Turn off. Wait half an hour. Turn back on to 600°F. This process takes about 2 hours. When the oven is hot the second time cover the pans and put them in the oven. Turn the oven down to 500°F. After 35 minutes, take off the covers. Bake for another hour. I always feel uneasy when new bakers ask me how to bake bread. I know what they want. They want a recipe like the ones you find in any modern cookbook, exacting and thorough, a recipe that says: mix so many ounces of flour, water, salt in this way for so many minutes; ferment for so long; shape just like this and you’re guaranteed a perfect loaf. But I can't give them a recipe. A recipe for sourdough is at best a teaching story, at worst a confusion of jargon and measurements that make baking sound more like nuclear engineering than the making of your daily bread (I’ve been guilty of the latter myself). All I can give them are approximations and metaphors: add some water, wait, and then, if you’d like, add a little more; ferment till the dough pops like rice crispies when pinched between your fingers; the bread is ready to bake when it feels light and delicate under the palm of your hand, unless it’s cold from the refrigerator, and then your guess is as good as mine. All I can tell them is to try and then try again. “When is my sourdough ready to use?” the new baker asks. “When it’s risen and just beginning to fall,” I say, and then stop to think. “But not always. That only works if it’s wet. Really, you need to taste it.” “Taste it?” says the new baker, his lip curling in mild distaste. “Yes!” Now I’m getting excited. This is a much better explanation. “Taste it! Your sourdough is ready when it’s bubbly and tastes bright sour, but not overpoweringly sour.” He stares at me in confusion. I deflate. “Well,” I say at last. “You can try dropping a spoonful in water. If it floats you know your bread will rise, eventually.” Even after six years and so many thousands—tens of thousands?—of loaves my own bread still refuses to be confined to neat recipes. Sure, I start with formulas measured out in careful grams and a fermentation schedule laid out in quarter hour intervals so I can track all my doughs across the day. But then my sourdough is young and mild so I add a bit extra to each batch; or the kitchen is warmer this week, even with the hood on, and I’m hurrying all morning to catch up; or the wheat dough I’m mixing feels different—less elastic, maybe?—so I hold back a little water, just to be safe. Even if the weather, the flour, the temperature of the water from the tap are all exactly the same from one week to the next, the doughs change. I still depend as much on intuition and attention as on those formulas and schedules. I still try, and sometimes fail, and try again. Sophie Owner | Baker TODAY AT MARKET and NEXT WEEK FOR MARKET PREORDER 10am – 2pm, 1100 Railroad Ave BREAD: Red & White ($7.50 / 720g) Mountain Rye ($7.50 / 750g) Vollkornbrot ($8 / 750g) Seedy Buckwheat ($8 / 420g) SWEETS: Gingersnap Cookies ($5 / 2) Chocolate Chip Hazelnut Cookies ($5 / 2) Oat Scone with Strawberries ($5 / ea) Rhubarb Cardamom Snack Cake ($5 / ea) Lemon Poppy Pound Cake ($20 / loaf) Brown Butter Shortbread ($9 / half dz) Hazelnut Shortbread ($9 / half dz) Next WEDNESDAY PICKUP Self-serve pickups in Birchwood, Columbia, Lettered Streets, South Hill, and Fairhaven. Address and directions with your pickup reminder email Wednesday morning. Order by Sunday night. Red & White Mountain Rye Toast: WILD & SEEDY Sweets: BITTERSWEET CHOCOLATE COOKIES + BLACK & WHITE SESAME CAKE Raven Breads is hiring a farmers market rep and a bakery assistant. These two part-time jobs start in April and could be combined by the right person into a single position. If you like bread and bicycles and want to be part of this little business as it grows, check out the job postings here. Last Wednesday through Friday I moved briefly down to Burlington to prep for and teach a two day workshop for the Bread Baker’s Guild on baking with local grains. We named the workshop after the first clause of Arthur Ashe’s famous and ever useful quote—“Start where you are, use what you have, do what you can.”—because the grain system, like every other part of the food system, is personal and political, economic and ethical, and endlessly, overwhelmingly complex. Mel, my co-teacher and the head baker at Grand Central Bakery, talked about wheat. I talked about rye. We both talked about enzymes and wet harvests, protein levels and why the commodity market is wrong about what makes “good” grain. Every time the questions got too technical we turned to our most over-qualified student, a lifelong baker and cereal scientist from OSU, and gave him the floor to expound on how nitrogen application effects protein content, or the role of the aleurone in sprouting grain. We baked breads and pastries with four kinds of wheat (Doris, Skagit 1109, Salish, Trailblazer) and two kinds of rye (Gazelle, Binto?), plus a little buckwheat on the side. Below is the recipe for the excellent wholemeal galette crust that we made for Friday breakfast and filled with roasted winter vegetables, goat cheese, and herbs, and which you’ve probably encountered at the Saturday farmers market filled with my summer fruit gleanings. Sophie Owner | Baker ALL PURPOSE GALETTE CRUST (probably adapted many years ago from a recipe by Dawn Woodward and/or Liz Prueitt) Makes two 9-10” galettes 160g whole wheat 45g whole rye 10g dark buckwheat 2g (½ tsp) salt 145g butter, cold 65g water, cold Mix as you would any pie crust. Chill. Roll into rounds. Add sweet or savory filling (approx. 350g filling per galette). Fold in the edges and brush the crust with a little yogurt, egg, or cream for shine. Bake at 400F for 20-30 minutes, or until the crust is golden and the filling, if fruit based, is bubbling nicely. This week in the WINTER BREAD SUBSCRIPTION: Red & White Mountain Rye Baker's Choice: Rye & Oat Westphalian Pumpernickel, the Baker's Choice loaf for March 25, is available for pre-order for another week. Because this bread takes almost three times as long to make, bake, and cool as my normal ryes, the order window closes next Sunday. On Wednesday night the middle school library filled up with adults. They were neighbors, school teachers and staff, grassroots organizers, college students from up the hill, city council members, civil servants, gardeners, and hunger relief workers. They lived in, worked in, organized in, grew food in, studied, or were curious about our neighborhood’s food desert. For me, the neighborhood acts as a collection of homes. I haven’t claimed or been claimed by these streets and schools. I’m a renter in a communal house, and therefore, by experience if not definition, impermanent. My neighbors are neighbors by proximity rather than daily contact; ours is a block of back yards, not front porches. I can come and go as I please because I have a bike, because, to me, $2 round trip bus fare is pocket change, because I can walk or run across the city and sometimes do. I haven’t thought much about our neighborhood food desert. When we circled the cafeteria tables to talk problems and solutions, I listened. I kept notes for the group. “Imagine money is no barrier,” the activity’s organizer told us. “What would you do?” And my table mates told me. They told me not only what they would do, but what they were doing. The most inspiring part wasn’t the ideas themselves, it was that, with or without funding, so many of them were already being implemented. Near the end, our Council rep stood up. “We can do all this,” she said, “but who will be living here to use the services?” And I could see it almost like it had already happened, because in so many neighborhoods it already has: the community-owned grocery, the parking lot farmers market, the network off urban gardens and food-share boxes, the scratch-made school lunches and community dinners, the vegetable truck with it’s tinny jingle, all the dreams and organizing and hard work, past and present, realized, and the neighborhood gone, flattened by gentrification. Sophie Owner | Baker TODAY AT MARKET Red & White Oat & Honey Mountain Rye Vollkornbrot Seedy Buckwheat Malted Chocolate Chip Cookie Bittersweet Chocolate Cookie Gingersnap Oat Scone Gingerbread Cake Shortbread Buckwheat Crisps FALL BREAD SUBSCRIPTION 9 weeks remaining Every Wednesday, OCT 2 - DEC 18 Pickup downtown, Birchwood, Fairhaven This week: Mountain Rye, Red & White, RING RYE We were talking the other day about the knowledge paradox of teaching. My friend, who teaches engineering and design to high school students, was explaining the new CNC software he was navigating. “Last year this program was so easy to teach,” he told me, “because I didn’t know how to use it either. This year...” and with a quick series of clicks he demonstrated his newfound proficiency. The router started spinning across the screen, tracing the design he’d laid out. “This year I know too much.” Just now, the stack of books by my bed includes a gardener's manifesto, a classic literary cookbook, a beautiful and cynical essay on the history of humankind, and Wendell Berry. In a week or two, the books will be different, but the stack will still lean heavily towards food and agriculture. Because so many of my friends, too, live lives built around food, I can often assume a deep and unspoken knowledge beneath our conversations. Without the shared obsession, where does the conversation begin? I want to explain this business to you, the why and the what of it, but where do I start? With the flavor and nutrition of sourdough? With agricultural politics? With environmental ethics? My relationship with food has been built over a lifetime. Which stories do I use to lay my foundations? Do I tell you about the garden I kept as a child and my friendships with trees? Or do I tell you about the sinking sensation of flying over the country for the first time after reading Cadillac Desert and watching the circle-square patchwork of central spigot irrigation spread over the landscape? Do I tell you how, after a farmworker friend told me about her father shepherding each of his daughters across the border in turn when they were teenagers, about the fear and loneliness and the bodies in the desert, about how she’s never been back home, I went to her half-empty village in the Mixe and her grandmother made me tortillas? Or do I tell you about our Sunday brunches, the pleasure I feel when I look around at a house full of friends and laughter, with the sun rising towards noon, and the table scattered with crumbs and empty coffee cups? I don’t have answers, but I’ll keep thinking about the questions. You think about them, too. Tell me about businesses you’ve encountered that effectively share their stories through advertising, design, mission statements, literature, or well trained staff. Learning to bake bread is only one part of building this business. Learning to teach people about bread might be just as important. See you soon. Sophie Owner | Baker TODAY AT MARKET Red & White Gleaner* Mountain Rye + Vollkornbrot Chocolate Malt Chocolate Chip Cookies Bittersweet Chocolate Cookies Oatmeal Scone Apple Cake Shortbread WEDNESDAY BREAD SUBSCRIPTION Cinnamon Twist Mountain Rye *a whole wheat bread made with: with apples from the last few trees of an orchard remnent in the county not yet overtaken by scrub forest; pears from my grandmother's house; dried champagne grapes our 80+ year old neighbor planted along the fence; dried concord grapes from what was once an urban homestead; dried plums from the back alleys of Sunnyland; and dried apricots from the farmers market, because apricots are a sadly ungleanable fruit in the Pacific Northwest. "But you are bakers, not scientists," Thomas reminded us as he finished explaining a graph of amylase activity and temperature. The whiteboard was covered with such graphs, as was the easel to its right. This science, he wanted us to remember, was a tool to add to our baking arsenal, alongside taste, smell, memory, and tradition. It could not define our work. At this point in the march of knowledge, a master baker still knows more with his hands about making good bread than do all the scientific publications combined. We were midway through a weeklong course titled Modern Bread Theory: A Scientific Focus, but because we were bakers, not scientists, we spent most of our days in the San Francisco Baking Institute's sprawling warehouse bakery, putting those classroom lectures into practice. I was lured by the science's apparent clarity. This view of wild fermentation, defined in pH, temperature, and well-understood enzymatic reactions, felt so readily masterable. I know, after all, now to read and synthesize scientific literature. It's what I was academically trained to do. But again and again, I watched Thomas put his hands on (or in) the dough to asses it's molecular workings through touch. "It's ready," he might tell us, "hurry." Or, "Turn the mixer up to second for a few minutes." Those hands, with their twenty years of baking practice, knew things I would never learn by reading. And besides, I'm not a scientist anymore. I'm a baker. Science, now, is not the end in and of itself, but a tool to better understand the practical workings of the world. Saturday Market Red & White, Mountain Rye, Vollkornbrot Bittersweet Chocolate and Malted Chocolate Chip Cookies Apple Cake Gingerbread Shortbread Wednesday Preorder WILD & SEEDY! Mountain Rye Shortbread Gingerbread See you soon!

Sophie Owner | Baker It started with a bread lesson. "Will you teach me to make bread?" one of my housemates asked. "Yes," I said. And then, after a pause, added slyly, "if teach me to use the sewing machine." And so the house skillshare, scheduled for an unspecified day in the dark of winter, was born. Now every time one of us demonstrates an interesting talent, that too is added to the list. Mixing craft cocktails. Speaking French. We have rather a lot of odd knowledge bumping around our collective heads. By the time winter comes, we may have to establish a school. Thinking about what parts of this craft are most essential to a home baker has been rather like pruning a knowledge tree. Each twig is budding with possibility, but to see the scaffolding of sturdy branches underneath, one must cut away the small wood. Only, how small is too small? What if the twig is especially lovely? I spend so much of my life looking out from between the branches that I sometimes can't see the tree for the leaves.. Out of this pruning and practice, I hope to emerge with some better sense of how to communicate the making of bread, or at least, the making of my bread. It is a specific variety, this tree of mine. A gnarly, russeted, late fall apple, perhaps, rather than a tidy dwarf tree with easy, smooth fruit. Or maybe I flatter myself. My bread is no Karmijn de Sonnaville. At least, not yet. Anyway, I think, after I get over my old terror of standing in front of the class (and standing around my kitchen with friends should be a good start), I would like to teach some bread classes. It is all very well to tell you what goes into my loaves, but even better to show you. What do you think? Would you like to learn something more of wholegrain sourdough? Saturday Market Red & White, Mountain Rye, Vollkornbrot, Country Rye Bittersweet Chocolate and Malted Chocolate Chip Cookies Black Sesame & Fennel Palmier Croissant Cinnamon Twist Granola + Shortbread Wednesday Order (due by Sunday night) Cinnamon Raisin Mountain Rye Brown Butter Shortbread See you soon! Sophie Owner | Baker POSTSCRIPT: OVERHEARD

Need one last push to get you off Facebook? Read this rather terrifying piece from the LRB. I should refrain from poking at controversial ideas at this hour of the morning, in public, before I’m quite ready to be politic or polite. I should, I know. But oh, I am contrary as a cat, and do so enjoy swatting at the curtains. So, here it is: I am dumbfounded, disturbed, distraught by the pervasiveness of scientific illiteracy. I’m reminded of it weekly at the farmers market by the dietary lectures I receive from customers and passers by. No, I say calmly, wheat is not toxic. Actually, I cut in, rye and barley also have gluten. Yes, I’m serious. So do the ancient wheats like emmer, spelt, and einkorn. Well, I reply, smiling with all my teeth, mutation drives evolution, as well as plant breeding, so no, I don’t think it’s "unnatural." And no, plant breeding that induces mutation with radiation does not produce “bad” food. (And dammit, stop trying to hide your fears behind pseudoscience! I refrain from adding, because I do have some small sense of self-preservation). But while swallowing the snake oil of quacks like Dr. William Davis and Dr. David Perlmutter may cause harm to people’s pocketbooks, and, more troublingly, to their food traditions, it’s no skin off my nose. Eat whatever makes you feel healthy, or safe, or morally superior. The problem is, scientific illiteracy doesn’t stop with the eager embrace of the latest dietary prophet cloaking their food religion in scientific terms. Respectable, mainstream media outlets consistently confuse hypothesis with theory, ignoring the complexity and contradiction of real science in favor of the easy story. Environmental and political activists (including those I respect and with whom I agree) often so abuse statistics as to undermine their credibility (and the maddening thing is, the science is there! There’s no need to cherry pick data on climate change or the public health consequences of economic inequality). The reason all this matters, the reason I get worried when a customer proselytizes their Google-searched diet, or when I read yet another article twisting a single study into Scientific Truth, is that such a fundamental misunderstanding of the scientific method and inability to distinguish science from pseudoscience leaves people vulnerable to truly dangerous anti-science campaigns like climate change denial and the anti-vax movement. The re-emergence of preventable diseases like rubella and diphtheria, and the lack of political will to reduce fossil fuel consumption even as we hurtle towards the apocalypse, are the inevitable consequence of such ignorance. Approach the world with curiosity and a critical eye. Ask questions. Challenge the orthodoxy of common wisdom. But oh, do so as an informed skeptic, and not as a dupe! All right. That’s enough damage done for one morning. If I’ve offended you, I hope you’ll challenge me rather than walking away. I don’t have time to debate with you at the farmers market, but send me an email, or invite me to coffee, and I’ll gladly engage! Saturday Market Red & White, Mountain Rye, Vollkornbrot, Country Rye Bittersweet Chocolate and Malted Chocolate Chip Cookies Black Sesame and Fennel Palmier Garden Pesto Twist Morning Bun Hazelnut Cake with Strawberries & Cream Granola Brown Butter Shortbread Wednesday Market Rosemary Sea Salt Mountain Rye Various pastries See you soon!

Sophie Owner | Baker When I was a child, I saw the magic at work in everything. The world was full of wonder, and the space between the physical and imagined was slim. There was little difference between the magic of tide pools, methodically explored in Tevas and fleece on an overcast afternoon, laminated species key in hand, and the magic of a backyard fairy land, where I might spend equally serious hours exploring the fairy kingdom and laying out offerings of flowers and tiny feasts in bowls carved from hard, green apples. I discovered worlds in the secret colors inside clam shells, in a geode's prickly center, in the lush abstractions of Georgia O'Keefe's erotic flowers, which I carried in a pocket-sized art book someone must have picked up at a museum gift shop. I kept beach stones and horse chestnuts for pets. But, of course, I grew up. In biology and physics classrooms, we learned the most beautiful theories, but never spoke of wonder. In English class, we read fiction, but wrote only critical essays. In turn, each subject closed its door on imagination. I learned many things in school, but forgot magic. Looking yesterday at the wild topography of the rye breads, I felt a sudden upwelling of nostalgia. The boules cooling on the rack before me were as beautiful as any purple-hearted clam shell. What stories might they hold? But it was a foolish question. If there are stories in my loaves, I will never find them now, grown up and educated as I am. And so I shook away the unsettling sense of loss and returned to my work. Saturday Market Red & White, Mountain Rye, Vollkornbrot, Country Rye Bittersweet Chocolate and Malted Chocolate Chip Cookies Nibby Chocolate & Hazelnut Sandwich Cookies Cardamom Rolls and Cinnamon Rolls Polenta Cake Granola Wednesday Market Red & White, Mountain Rye Bittersweet Chocolate and Malted Chocolate Chip Cookies Rolls of some variety Possibly something with strawberries Granola See you soon!

Sophie Owner | Baker How do we know who we are, except by how we live? Marilynne Robinson asked in my ear. I stopped, elbow deep in the dough, because it was, I realized, the very question I ask myself every day in a dozen different ways. It is the heart of small, everyday decisions about how to move through the world, and large, existential decisions about work and place and community. Who do I want to be, and how do I live as that better self? And then the forward march of Robinson's powerful mind and the immediacy of the task in front of me pulled me back into motion. Sometimes someone else articulates a thought or feeling you didn't know you had until you heard it said, and then it's so obvious, so fundamental, that you cannot imagine it unknown. We live much of our lives feeling alone in ourselves, even when surrounded by other people. The reminder that we are never truly alone, that someone else in the world, or many someones, holds in themselves the same experience, can come with a profound sense of recognition. It is a beautiful intimacy, to be so connected, even if it is across satellites, over centuries, or though the pages of a book. When I was young I was baffled by the singularity of being myself. Why am I only this girl, and no one else? I asked. It seemed to me that I might just as easily wake up tomorrow in another mind and body. A soul was such an essential thing to be tied forever to so ephemeral and mundane a vessel (though of course I understood this in much simpler terms—if only I had kept a journal at eight!). This was also a time when I thought often about death—my own—with great curiosity and no fear. It was certainly the most mystic period of my life, in those early days of self-consciousness, when I could not understand myself separate from the universe, before I learned the designated boundaries of self and mind. And why, I wonder, did the adult world feel it so imperative to teach me those boundaries? Why did they insist I learn to be alone? Perhaps when I reach for poets like William Stafford and Mary Oliver, when reading Wendell Berry fills me so deep with joy and grief that the familiar words bring me to tears, I am reaching also for this forgotten understanding of myself in the world. I read a psychology paper sometime early in my undergraduate arguing that we cannot have complex feelings without the words to articulate them. At the time we were also reading about deaf children raised without sign language, and the idea that their lack of language might leave them trapped not only in literal but also in mental silence was so hurtful that I wanted to reject the entire field of cognitive linguistics out of hand. Now, looking at the way that words have shaped my understanding of myself, I find the hypothesis compelling. How do we know who we are, except by how we live? Or maybe, how do we decide how to live, except by defining ourselves? At Market Today Red & White, Mountain Rye, Vollkornbrot, Country Rye Bittersweet Chocolate and Malted Chocolate Chip Cookies S'mores on Nibby Chocolate Wafers Cardamom, Dark Chocolate, and Raspberry Rolls Rhubarb Polenta Upside Down Cake Granola Preorder Wednesday Pickup Red & White Mountain Rye Cinnamon Raisin Bittersweet Chocolate Cookies See you soon!

Sophie Owner | Baker |

BY SUBJECT

All

|